|

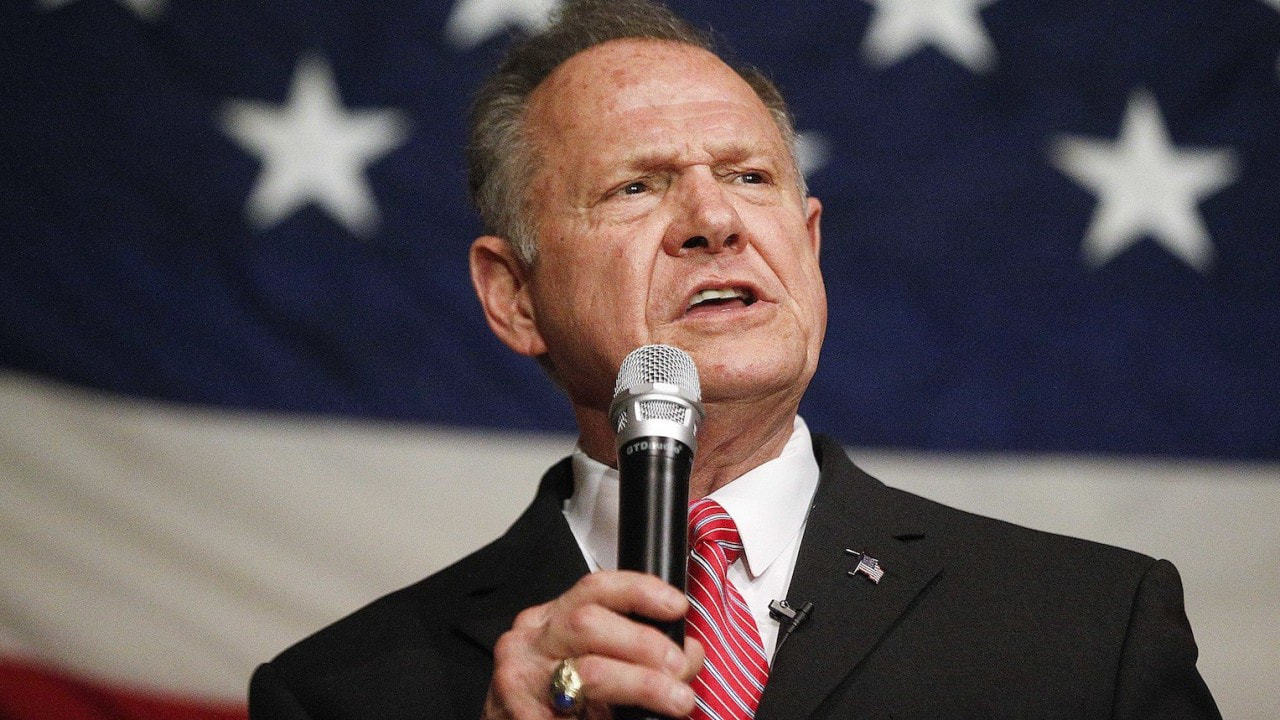

We weren’t surprised to find the follow-up coverage of the Alabama Senate election was slanted. Slant in and of itself is limiting because it promotes one perspective while invalidating others. The four articles we analyzed had an additional component: questionable logic was hiding behind the bias. Here are three examples and how each can limit our thinking. The blame game Breitbart cited eight journalists who commented on President Donald Trump’s supposed role in the election outcome, as well as that of his former adviser Steve Bannon. In fact, this is how the article begins: Mainstream media journalists on Twitter Tuesday quickly looked to blame President Trump for Republican Judge Roy Moore’s [loss] in the Alabama Senate race — a narrative likely to become the next mainstream media talking point. Do you know how to turn something into the “next mainstream media talking point”? Writing about it just that way. It’s true that the quotes blamed Trump and/or Bannon for Moore’s loss (Reuters included similar quotes in its article), and Breitbart used the quotes to come to Trump and Bannon’s defense. Yet engaging in tit-for-tat obscures the questionable logic behind the blame, which is that any one person can determine the outcome of an election in which more than 1 million people voted. It’s all smooth sailing from here NPR and Politico promoted the idea that because a Democrat won a Senate race in the state of Alabama (which hasn’t happened in 25 years), Democrats will somehow win more elections next year. Here’s an example from NPR. Democrats are hoping this fired-up coalition will help them make gains in the House, Senate and governors’ races all over the country next year. Maybe some Democratic lawmakers believe this, but it doesn’t follow, nor are elections that simple. Future election results will depend on a number factors, including how much a political party engages with voters, as well as how it appeals to them in terms of specific policies. Let’s throw due process out the window while we’re at it All of the articles mentioned the sexual misconduct allegations against Moore and the possible problems Congress would have had to contend with if he were elected. Some lawmakers said or implied Moore’s loss helped them “dodge” the problem, and Politico and NPR suggested the same. The latter outlet wrote: Sure, their razor-thin majority in the Senate just got one vote smaller, but now they won’t have to answer why they have an accused child molester in their midst. They won’t have to wrestle with the question of whether to seat Moore, investigate him or expel him. This perspective is limiting in two ways. One, it suggests it’s better to avoid a problem than to face it head on. And two, emphasizing the supposed upsides of avoiding the problem and using terms like “accused child molester” to describe Moore hide the fact that he’s being tried in the court of public opinion, rather than through due process. (Read this for more on this subject.) Bias can be hard to detect, because it tends to hide between the lines. When questionable reasoning is involved, it’s a two-way street: the reasoning promotes the bias, and the bias makes the reasoning harder to spot. But once you see how the two work together, it’s easier to identify both types of distortion in anything you read. Comments are closed.

|

Jens Erik GouldJens is a political, business and entertainment writer and editor who has reported from a dozen countries for media outlets including The New York Times, National Public Radio and Bloomberg News Archives

February 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed