|

In a Jan. 2017 interview, economist, physicist and mathematician Eric Weinstein said, “At the moment, we’re in this crazy narrative over fake news, where fake news is supposed to be limited to things that are just made up and untrue. But the problem is … how many different ways does [the] news manipulate us into thinking something that isn’t true, or shading our feelings or emotions?” According to Weinstein, there are four kinds of “fake news”: Narrative, algorithmic, institutional and false news. In a Jan. 2017 interview, economist, physicist and mathematician Eric Weinstein said, “At the moment, we’re in this crazy narrative over fake news, where fake news is supposed to be limited to things that are just made up and untrue. But the problem is … how many different ways does [the] news manipulate us into thinking something that isn’t true, or shading our feelings or emotions?” According to Weinstein, there are four kinds of “fake news”: Narrative, algorithmic, institutional and false news.

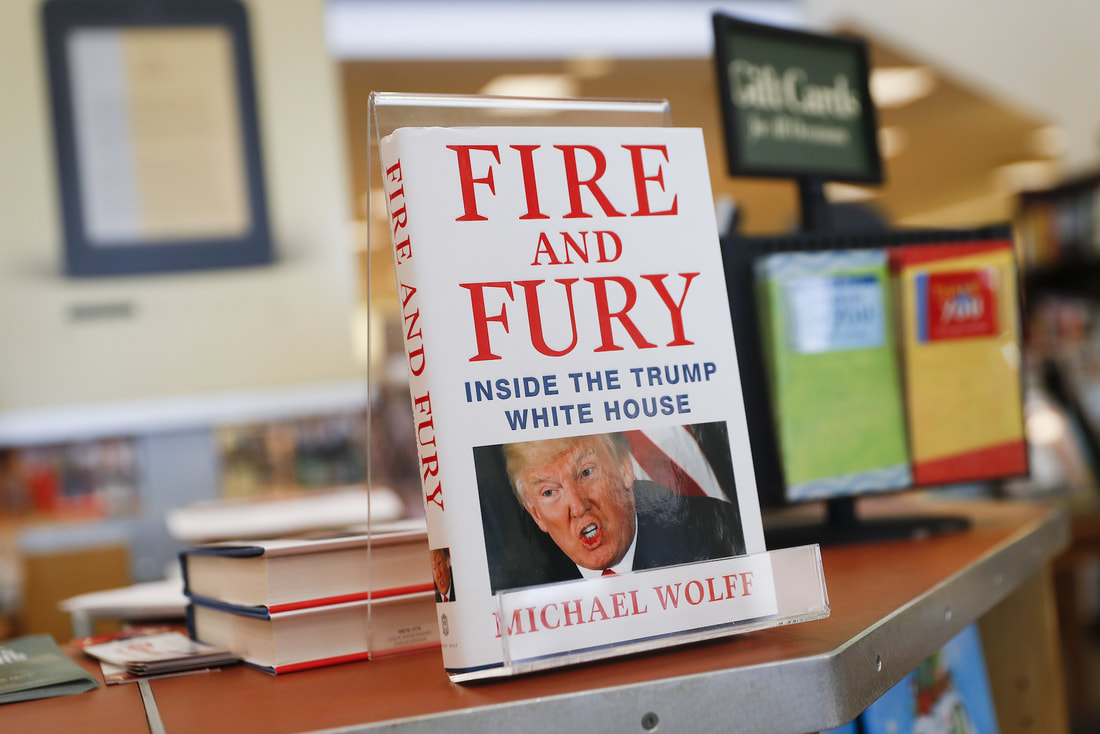

We saw a relationship between Weinstein’s distinctions and The Knife’s analysis process — particularly slant. So we further explored his four categories, how they relate to our analysis, and applied them to recent news coverage. Given the media’s significant response to Michael Wolff’s book “Fire and Fury” and Trump’s subsequent tweets, we chose this as our subject matter. We’ll also look at two additional kinds of distortion: spin and faulty reasoning. NarrativeHillary is going to win, it’s inevitable – remember hearing or reading some version of this during the 2016 elections? Weinstein uses this as an example of narrative-driven “fake news.” With this kind of bias, news outlets aren’t reporting information that is factually incorrect; rather, they mainly present only one, often narrow, viewpoint. This is an example of slant, or presenting news from a particular angle in a biased way. In the coverage we analyzed of Trump’s recent tweets, there were two main narratives: The New York Times and CNN: Trump’s tweets are proof that he is mentally unstable. Fox News and Breitbart: Wolff’s book is, as Trump put it, a “work of fiction” and the media is again spreading fake news. Both narratives were highly slanted. In fact, all four outlets received slant ratings above 70 percent (the higher the score, the more they reinforced the narrative). Here are some examples of how these two narratives came to be. The New York Times is fairly explicit with its opinion about Trump, which supports its narrative. For example, The New York Times says, “Mr. Trump’s self-absorption, impulsiveness, lack of empathy, obsessive focus on slights, tenuous grasp of facts and penchant for sometimes far-fetched conspiracy theories have generated endless op-ed columns, magazine articles, books, professional panel discussions and cable television speculation.” Note how this is stated as though it were fact, but it is actually The Times’ opinion. How Fox News and Breitbart form their narrative may be harder to spot. They support it by mostly presenting one viewpoint: Trump’s. As a result, his perspective becomes the main narrative for these outlets. So what are some other viewpoints? One is that Trump’s tweets may not necessarily be a sign of mental illness, but rather a conscious or intuitive strategy. Weinstein suggests, for example, that Trump is adept at using persuasion. He says others, such as Scott Adams, used this understanding to predict Trump would win the election. Considering different viewpoints and evaluating their merits is a part of critical thinking, but the media interferes with this process by emphasizing some points of view and deemphasizing others. InstitutionalAccording to Weinstein, it can be hard to criticize opinions that come from large, well-known institutions such as Harvard or the Brookings Institute, saying organizations like these “can sort of release what [they] claim to be objective fact and [are] given this extremely courteous reception.” But he said such institutions are also capable of “suppress[ing] some findings and accentuat[ing] others,” thereby “filter[ing] reality.” Perhaps a close cousin of this form of bias, which we discuss often in The Knife, is when media outlets include a single expert opinion, or multiple experts with a similar bias, that supports a particular point of view. In such cases, who are we, the non-experts, to disagree? For example, CNN quotes forensic psychiatrist Bandy X. Lee who said on Thursday that Trump “is showing signs of impairment that the average person could not see.” But what about the experts who disagree with Lee’s position, like Allen Frances, who helped write the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the main tool mental health professions use to make diagnoses. He said professionals “shouldn’t be diagnosing at a distance, and they don’t know what they’re talking about.” Alternative views like this one were missing from CNN’s coverage, which contributed to it being highly slanted in our ratings. AlgorithmicIn many cases, our news is now being curated for us by algorithms, or the rules computers follow to make a decision, such as which news to show you. An example is Facebook’s news feed. Based on what you click on, like and share, among other things, Facebook decides what to show you and what not to, and where to put it in your feed. This is outside the domain of traditional news sites, but is still something that can affect our perception of the world. For example, if users mostly click on conservative sources in their feeds, or they mostly share conservative sources, Facebook’s algorithm may decide to show them more conservative news sources. Over time, my feed may become an echo chamber of conservative views. So when Wolff’s book comes out, I may mostly see comments criticizing it and think this is the prevailing judgement of the book. False newsThis is when a story, or parts of it, is completely fabricated. Fact-checking is the standard defense against this kind of fake news, although some stories still fall through the cracks. Remember Pizzagate? The Knife looks for false news as part of its data analysis, but it also looks at cases where the media was inaccurate or misleading in how it reported the facts. You can read our weekly round up of top media errors for this week here. SpinThe Knife’s spin analysis looks at how words or phrases promote a certain viewpoint. Although he didn’t mention it as one of his four kinds of fake news, Weinstein touches on the concept of spin when he discusses Russel Conjugation, or emotive conjugation. In an article, Weinstein explains that emotive conjugation is a concept from linguistics and psychology that explains how words and phrases have both factual content (e.g. their dictionary definition) and an emotional or feeling content (the impressions we get from certain words). As a result, words and language can be used to manipulate opinions without falsifying facts. For example, Weinstein uses the example of calling someone a “whistle-blower” versus a “tattletale.” Both are synonyms and share the same factual content, but the former is likely to give a more positive feeling than the latter. Our team of analysts examined how this played out in the coverage of Wolff’s book and Trump’s tweets on Saturday. For example: Wolf’s book “questions Trump’s emotional and intellectual competence.” (Fox News) Trump was “coming off a week of heightened scrutiny over his mental health.” (CNN) Although neither are particularly positive, do you get a different feeling from Trump’s critics questioning his “competence” compared to his “mental health?” One implies a question of ability, the other a question of illness. The spin ratings for Breitbart, The Times, CNN and Fox News, respectively, were 86, 81, 79, 65 percent* (higher means more spun). *Note: in our current ratings system, outlets are penalized equally for including spin in their own words and including spin within quotes. Faulty ReasoningOne kind of distortion Weinstein didn’t touch on in his interview, but one we think he would probably agree with, is faulty reasoning. This commonly happens when news outlets use logical fallacies to make a point, such as drawing hasty conclusions from incomplete information. Take this one, for example: We can reliably deduce people’s mental processes from their tweets or what they say. Although the outlets don’t directly make this argument, it is something that a reader might infer from the narrative that Trump’s tweets show he is mentally unstable. While it’s possible to make rational hypotheses and predictions about a person’s thought process, we can’t know it for certain, at least not with our current technology. As Weinstein points out, people don’t always mean what they say literally, and human behavior is a complex subject. Equipping readers with better toolsWeinstein says he’s “trying to get the power tools into the hands of the people” and that he wants to “upgrade” their relationship with the media so that they don’t feel dependent on the news to tell them what to feel about certain topics. We couldn’t agree more. Comments are closed.

|

Jens Erik GouldJens is a political, business and entertainment writer and editor who has reported from a dozen countries for media outlets including The New York Times, National Public Radio and Bloomberg News Archives

February 2018

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed